| World Journal of Oncology, ISSN 1920-4531 print, 1920-454X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, World J Oncol and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.wjon.org |

Original Article

Volume 6, Number 1, February 2015, pages 265-269

Liver Metastases in Prostate Carcinoma Represent a Relatively Aggressive Subtype Refractory to Hormonal Therapy and Short-Duration Response to Docetaxel Monotherapy

Arsh Singha, Naga K. S. Cheedellaa, Shams A. Shakila, Frederick Gulmib, Dong-Sung Kimc, Jen C. Wanga, d

aDivision of Hematology/Oncology, Brookdale University Hospital Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY, USA

bDepartment of Urology, Brookdale University Hospital Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY, USA

cDepartment of Pathology, Brookdale University Hospital Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY, USA

dCorresponding Author: Jen C. Wang, Division of Hematology/Oncology, Brookdale University Hospital Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY 11212, USA

Manuscript accepted for publication February 25, 2015

Short title: Liver Metastases in Prostate Carcinoma

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/wjon903w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: We report a single institution’s experience from a small series of patients suggesting that liver metastasis in metastatic castration-refractory prostate cancer (mCRPC) represents a relatively aggressive subtype that is refractory to hormonal manipulation treatment, including luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist (LA) and abiraterone (Ab) therapy, although docetaxel is briefly effective.

Methods: Between 2007 and 2013, six patients with prostate cancer with liver metastases were analyzed. Biochemical response was defined as > 50% decrease in prostate-specific antigen (PSA) value.

Results: Two patients who presented with liver metastases died in less than 3 months after LA therapy. Two out of three patients (one died while receiving chemotherapy) received Ab after chemotherapy did not show any response and died while on therapy. One patient who presented with lung metastases initially received LA therapy and progressed on it with liver metastases in < 6 months. Thus, five of six patients did not respond to hormone therapy including LA and Ab. Three patients who received docetaxel after LA therapy had more than 50% objective PSA response with a mean survival of 4 months.

Conclusions: No literature addresses the response to hormone treatment in hepatic metastasis in prostate carcinoma. This small series suggests that liver metastases in prostate carcinoma represent a relatively aggressive subset against which hormonal therapy, including the LA and Ab, appears to be ineffective. Although our patients responded to docetaxel chemotherapy, their responses were of short duration. A further clinical trial involving more patients will be necessary to substantiate our findings.

Keywords: Hepatic metastasis; Prostate carcinoma

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Prostate cancer is the second most common cause of cancer death in men both in the United States and Europe. Approximately one in six men in the United States will develop prostate cancer. Roughly 30% of all newly diagnosed cancers in males are prostate cancer [1]. The estimated number of new cases of prostate cancer in the United States for 2013 is 238,590, and the estimated number of resulting deaths is 29,720 [1]. The high incidence/mortality ratio (8:1) suggests that the disease is lethal for only some men. Autopsy series have shown prostate cancer prevalence from 16.1% to 33.3% [2, 3]. Also, not all patients who harbor prostate cancer develop clinical disease. Histological evidence of prostate cancer has been shown through autopsy studies to be present in 30% of men above the age of 50 [4]. However, only 9% of these men actually develop clinical disease [4]. These facts not only highlight a variable clinical course of prostate cancer but also reflect a broad spectrum of tumor biology and its behavior.

Prostate cancer requires a risk-adapted approach in which therapeutic options are distinct, depending on clinical states from pre-diagnosis to death. Our understanding of the disease shows that, in some patients, the risk of death from non-cancer-related causes exceeds that of prostate cancer while in others, especially symptomatic metastatic castration-resistant prostate carcinoma (mCRPC), a more aggressive and immediate intervention is required. This speaks to the biology of this disease, which for the most part remains elusive. Here, we report a single institution’s experience from a small series of patients suggesting that liver metastasis in mCRPC represents a relatively aggressive subtype that is refractory to hormonal manipulation treatment, including luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist (LA) and abiraterone (Ab) therapy, although docetaxel is briefly effective.

| Patients and Method | ▴Top |

Data were retrospectively collected from our institution’s medical records department specifically for patients with metastatic prostate cancer from 2007 to 2013. Six patients who developed liver metastasis during the course of their disease were identified. Liver metastasis was histologically confirmed in five out of six patients, while one was confirmed radiologically. Charts were thoroughly reviewed, and patients were followed from the time of diagnosis of liver metastasis until the preparation of this manuscript. Patients’ characteristics collected were age, date of original prostate cancer diagnosis, Gleason score, performance status, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) value and its trend, time until progression, time until liver metastasis, treatment given, response to treatment, number of cycles of chemotherapy if given, histological and radiological features of metastasis, ALP, ALT/AST, Hb, and survival after liver metastasis development with or without treatment. Survival was defined as the time from the date of diagnosis of liver metastasis until the date of death or last follow-up. PSA response was defined as at least a 50% decline in PSA value after the start of treatment. All radiological images were viewed and reviewed with a certified radiologist. Histological and immunohistochemical studies of liver biopsies were stained with neuroendocrine marker to exclude neuroendocrine tumor. The polyclonal antibodies used were mainly CD56, chromogranin-A, synaptophysin, thyroid transcription factor (TTF-1), PSMA, PSA, CAM5.2, CDX2, CEA, CK7, and CK20.

| Results | ▴Top |

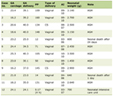

In the data collected retrospectively at our institution from 2007 to 2013, we identified six patients with prostate cancer who developed liver metastasis at some point during their disease course. The clinical characteristics of these six patients are shown in Table 1. Median age at the time of liver metastasis was 68.5 years. The ECOG performance status was generally good. Gleason score was at least 8 in four out of six patients (two unknown) and median PSA was 149, suggesting an aggressive disease from the onset. Although median PSA value at diagnosis of prostate cancer was 149, the median PSA at the time of liver metastasis was lower at 100.5, likely reflecting the effect of hormonal therapy. At the time of diagnosis of prostate cancer, two patients did not have metastatic disease; among the four who presented with metastatic disease, two had metastasis to bone while the third patient had metastasis to bone and liver. The fourth patient was diagnosed with metastasis to liver, bone, and lung. The median time to development of liver metastasis was 15.5 months.

Click to view | Table 1. Patient Characteristics Prior to and at the Time of Diagnosis of Liver Metastasis |

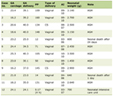

In the five patients with histological confirmation of liver metastasis, we ruled out neuroendocrine differentiation of the prostate cancer at the metastatic site after reviewing liver biopsies with the pathologist for histological and immunohistochemical studies. The five specimens did not show any neuroendocrine or small cell carcinoma differentiation (Table 2). All adenocarcinoma were positive for either PSA and/or PSMA on IHC while none expressed chromogranin-A, synaptophysin, or CD56 (N-CAM) except one focally positive for synaptophysin. Focal positivity for synaptophysin was seen in very few cells and was considered nonspecific [5].

Click to view | Table 2. Pathological Analysis of Liver Metastasis |

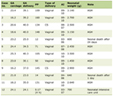

All the patients were started on LA therapy at the time of diagnosis. Four patients progressed on LA therapy, and two patients died on LA therapy within 3 months. Among those four patients who progressed on LA therapy, three received chemotherapy on progression with liver metastasis. As the duration of response was short to docetaxel, two of three patients received Ab after progression on chemotherapy and died while taking the Ab. The third patient died while on chemotherapy. The fourth patient is alive with stable disease (enzalutamide was started after LA therapy) (Table 3).

Click to view | Table 3. Outcome of Patients Treated With Hormone |

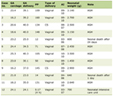

Chemotherapy of choice was docetaxel (75 mg/m2, every 3 weeks with prednisone) in three patients, as mentioned above. Median number of cycles given was 4 (range 3 - 6 cycles). A PSA drop of > 50% was seen in two patients while one had a > 90% decrease on docetaxel. Median survival times as calculated from the time of diagnosis of prostate cancer to death and from development of liver metastasis to death were 3.25 years and 4 months, respectively; none had treatment-related deaths.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Prostate cancer has a well-known predilection for bony metastasis. In a single institution retrospective analysis of 10 years, 620 cases of prostate cancer were reviewed, out of which only 30 cases of liver metastasis were found (4.7%) [6]. In another recent series (1,045 patients) presented as an abstract at the 2012 ASCO annual meeting by Kelly et al, the incidence of hepatic metastasis was only 5.6% [7]. Therefore, hepatic metastasis represents a rare occurrence. Neuroendocrine differentiation is often seen in prostatic adenocarcinoma and is hypothesized to result from long-term androgen deprivation therapy [8, 9]. To rule out liver metastasis of neuroendocrine origin in our patients, liver biopsy specimens of five patients were examined and found to be negative for neuroendocrine markers.

Median overall survival in our patients after development of liver metastasis was only 4 months. Another series of 28 patients by Pouessel et al showed a median overall survival of 6 months only after development of liver metastasis [10]. In a much larger series of 1,045 patients presented by Kelly et al [7], median survival of 14.4 months was reported in patients with liver metastasis compared to 22.2 months without liver metastasis. Therefore, development of liver metastasis in patients with prostate adenocarcinoma represents an ominous prognosis.

To date, no literature is available specifically regarding hormonal therapy or chemotherapy in the treatment of liver metastasis secondary to prostate carcinoma. In our small series of six patients (Table 3), we found that two patients who presented with liver metastasis deteriorated rapidly despite LA therapy and died in 2.5 months and 3 months, respectively, prior to the initiation of any other form of therapy; of three patients who developed liver metastasis early in the course of LA therapy, two were treated with Ab and progressed. Our fifth patient progressed to liver metastasis within 6 months of LA therapy and recently started enzalutamide. He continues to be monitored closely. All of our six patients showed no response to hormonal therapy, i.e., LA or Ab. This observation suggests that hormonal manipulation with either LAs or Ab therapy is not effective in the setting of liver metastasis. The response to androgen receptor antagonist therapy in such a setting is currently unknown. It will be interesting to see the long-term response of our chemonaive patient on enzalutamide.

In our series, three out of six patients who received chemotherapy showed good response; two of these patients showed a PSA decrease of more than 50% while the third patient had more than 90% decrease. However, these responses were of short duration (Table 4). In Kelly et al series, 55% of patients with liver metastasis responded to docetaxel chemotherapy compared with 64% who did not have liver metastasis [7]. In another series of 14 patients presented at a 2011 symposium in abstract form, an alternate regimen of epirubicin, cisplatin, and fluorouracil was used in patients with liver metastasis. Although a higher response rate was achieved, it was of short duration [11]. No literature addresses the response to hormone treatment in hepatic metastasis in prostate carcinoma including two large series of reports [7, 12]. We speculate here that liver metastasis in prostate carcinoma does not respond to hormonal manipulation therapy (LAs or Ab). It does respond to cytotoxic chemotherapy, but the responses are brief. A larger series of patients is needed to substantiate our speculation.

Click to view | Table 4. Treatment With Chemotherapy |

Approximately 67% of patients with prostate carcinoma are initially responsive to androgen deprivation therapy [13, 14]. One-third of treated prostate cancer patients experience recurrence and will progress into castrate-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) [15]. Numerous studies have shown that androgen receptor (AR)-mediated signaling plays an important role in the development of CRPC, which may render prostate cancer cells resistant to treatment [16, 17]. The possible mechanisms are AR overexpression, AR amplification, or AR mutation. These mechanisms are hypothesized to be the driving force behind progression of prostate cancer even in the presence of minimal androgen levels [18, 19]. An alternative mechanism of AR activation has also been described as cross-talk with other cellular signaling pathways leading to tumor growth and CRPC progression [20-23]. The latest finding regarding the AR-V7 mutation, which is resistant to enzalutamide and Ab, is the prime example [24]. Since liver metastasis in prostate cancer represents an aggressive subset, these AR mutations, overexpression, amplification, and cross-talk mechanisms may explain the refractory nature of such patients to hormonal agents. A detailed study of AR mutation, amplification, and other cross-talk pathways will be necessary to answer these questions.

Our patients’ characteristics of high Gleason score (Table 1) and absence of PSA staining in the liver in most of our patients is indicative of high-grade malignancy [25]. Whether there is a correlation between such high-risk characteristics and liver metastasis cannot be determined from our small study. Any future validation of this hypothesis will need to involve more cases.

Conclusion

Liver metastasis in patients with mCRPC represents a subset with poor outcome. Scant data are available on managing such patients. Our single-institution retrospective study of six patients with liver metastasis suggests that such patients represent an aggressive subset of prostate cancer patients who do not respond to hormonal therapy (LA and Ab). Although they may respond biochemically to docetaxel, the responses are of short duration. A larger, multicenter data set should be collected and reviewed to better characterize this aggressive subset of mCRPC with an aim to explore and identify an alternative therapeutic regimen for these patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest with any pharmaceutical company. Arsh Singh and Naga K. S. Cheedella are both first authors with equal contribution to the manuscript.

| References | ▴Top |

- www.cancer.gov.

- Sanchez-Chapado M, Olmedilla G, Cabeza M, Donat E, Ruiz A. Prevalence of prostate cancer and prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia in Caucasian Mediterranean males: an autopsy study. Prostate. 2003;54(3):238-247.

doi pubmed - Bubendorf L, Schopfer A, Wagner U, Sauter G, Moch H, Willi N, Gasser TC,

et al . Metastatic patterns of prostate cancer: an autopsy study of 1,589 patients. Hum Pathol. 2000;31(5):578-583.

doi pubmed - Scardino PT. Early detection of prostate cancer. Urol Clin North Am. 1989;16(4):635-655.

pubmed - Ather MH, Abbas F, Faruqui N, Israr M, Pervez S. Correlation of three immunohistochemically detected markers of neuroendocrine differentiation with clinical predictors of disease progression in prostate cancer. BMC Urol. 2008;8:21.

doi pubmed - Vinjamoori AH, Jagannathan JP, Shinagare AB, Taplin ME, Oh WK, Van den Abbeele AD,

et al . Atypical metastases from prostate cancer: 10-year experience at a single institution. Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199(2):367-372.

doi pubmed - Kelly WK, Halabi S, Carducci M, George D, Mahoney JF, Stadler WM, Morris M,

et al . Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial comparing docetaxel and prednisone with or without bevacizumab in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: CALGB 90401. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(13):1534-1540.

doi pubmed - Molenaar JP, Baten A, Blokx WA, Hoogendam A. Development of carcinoid tumour in hormonally treated adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Eur Urol. 2009;56(5):874-877, quiz 876.

doi pubmed - Bleichner JC, Chun B, Klappenbach RS. Pure small-cell carcinoma of the prostate with fatal liver metastasis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1986;110(11):1041-1044.

pubmed - Pouessel D, Gallet B, Bibeau F, Avances C, Iborra F, Senesse P, Culine S. Liver metastases in prostate carcinoma: clinical characteristics and outcome. BJU Int. 2007;99(4):807-811.

doi pubmed - Gupta S, Potvin KR, Whiston F, Winquist E. ECF chemotherapy for liver metastasis due to castration resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(suppl 7):abstr 175. Genitourinary Cancers. 2011 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium.

- Halabi S, Kelly WK, Zhou H, Armstrong AJ, Quinn D, Fizazi K,

et al . The site of visceral metastases (mets) to predict overall survival (OS) in castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) patients (pts): A meta-analysis of five phase III trials. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:5s, suppl; abstr 5002. - Perlmutter MA, Lepor H. Androgen deprivation therapy in the treatment of advanced prostate cancer. Rev Urol. 2007;9(Suppl 1):S3-8.

pubmed - Maximum androgen blockade in advanced prostate cancer: an overview of the randomised trials. Prostate Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group. Lancet. 2000;355(9214):1491-1498.

doi - Harris WP, Mostaghel EA, Nelson PS, Montgomery B. Androgen deprivation therapy: progress in understanding mechanisms of resistance and optimizing androgen depletion. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2009;6(2):76-85.

doi pubmed - Holzbeierlein J, Lal P, LaTulippe E, Smith A, Satagopan J, Zhang L, Ryan C,

et al . Gene expression analysis of human prostate carcinoma during hormonal therapy identifies androgen-responsive genes and mechanisms of therapy resistance. Am J Pathol. 2004;164(1):217-227.

doi - Shah RB, Mehra R, Chinnaiyan AM, Shen R, Ghosh D, Zhou M, Macvicar GR,

et al . Androgen-independent prostate cancer is a heterogeneous group of diseases: lessons from a rapid autopsy program. Cancer Res. 2004;64(24):9209-9216.

doi pubmed - Tamura K, Furihata M, Tsunoda T, Ashida S, Takata R, Obara W, Yoshioka H,

et al . Molecular features of hormone-refractory prostate cancer cells by genome-wide gene expression profiles. Cancer Res. 2007;67(11):5117-5125.

doi pubmed - Koivisto P, Kononen J, Palmberg C, Tammela T, Hyytinen E, Isola J, Trapman J,

et al . Androgen receptor gene amplification: a possible molecular mechanism for androgen deprivation therapy failure in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1997;57(2):314-319.

pubmed - Chen CD, Welsbie DS, Tran C, Baek SH, Chen R, Vessella R, Rosenfeld MG,

et al . Molecular determinants of resistance to antiandrogen therapy. Nat Med. 2004;10(1):33-39.

doi pubmed - Seruga B, Ocana A, Tannock IF. Drug resistance in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8(1):12-23.

doi pubmed - Yeh S, Kang HY, Miyamoto H, Nishimura K, Chang HC, Ting HJ, Rahman M,

et al . Differential induction of androgen receptor transactivation by different androgen receptor coactivators in human prostate cancer DU145 cells. Endocrine. 1999;11(2):195-202.

doi - Gregory CW, He B, Johnson RT, Ford OH, Mohler JL, French FS, Wilson EM. A mechanism for androgen receptor-mediated prostate cancer recurrence after androgen deprivation therapy. Cancer Res. 2001;61(11):4315-4319.

pubmed - Emmanuel S. Antonarakis, Changxue Lu, Hao Wang, Brandon Luber, Mary Nakazawa, Yan C, et al. Androgen receptor splice variant, AR-V7, and resistance to enzalutamide and abiraterone in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). Prostate Cancer 5001 J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:5s, suppl; abstr 5001.

- Leibovici D, Spiess PE, Agarwal PK, Tu SM, Pettaway CA, Hitzhusen K, Millikan RE,

et al . Prostate cancer progression in the presence of undetectable or low serum prostate-specific antigen level. Cancer. 2007;109(2):198-204.

doi pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

World Journal of Oncology is published by Elmer Press Inc.