| World Journal of Oncology, ISSN 1920-4531 print, 1920-454X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, World J Oncol and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.wjon.org |

Review

Volume 12, Number 4, August 2021, pages 85-92

Personalized Medicine in Ovarian Cancer: A Perspective From Mexico

Luis E. Fernandez-Garzaa , Irma G. Dominguez-Vigilb, Jose Garza-Martinezc, Erick A. Valdez-Aparicioa, Silvia A. Barrera-Barrerad, Hugo A. Barrera-Saldanaa, e, f

aInnbiogem SC/Vitagenesis SA at National Laboratory for Services of Research, Development, and Innovation for the Pharma and Biotech Industries (LANSEIDI) of CONACyT Vitaxentrum Group, Monterrey, Nuevo Leon, Mexico

bLaboratory for Translational Research, Rudy L. Ruggles Biomedical Research Institute, Nuvance Health, Danbury, CT, USA

cTecnologico de Monterrey, Monterrey, Nuevo Leon, Mexico

dNational Institute of Pediatrics, Mexico City, Mexico

eCenter for Genomic Biotechnology of National Polytechnic Institute, Reynosa, Tamaulipas, Mexico

fCorresponding Author: Hugo A. Barrera-Saldana, Innbiogem SC/Vitagenesis SA, Blvd. Puerta del Sol 1005, Colinas de San Jeronimo, Monterrey, N.L. 64630, Mexico

Manuscript submitted April 16, 2021, accepted April 26, 2021, published online July 10, 2021

Short title: Personalized Medicine in Ovarian Cancer

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/wjon1383

- Abstract

- Introduction

- The Role of Genetics in OC

- PM

- Mexico in the Fight Against OC

- Achievements of the PM in Mexico

- Challenges of the PM in Mexico

- Genetic Counseling: The Big Next Step for a PM in Mexico

- Conclusions

- References

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Ovarian cancer (OC) represents a serious health problem worldwide. In Mexico, most OC patients are detected at late stages, consequently making OC one of the leading causes of death in women after reaching puberty. Personalized medicine (PM) provides an individualized therapeutic opportunity for treating each patient relying on “omic” tools to match the correct drug with the specific pathogenic genomic signature. PM can help predict the best therapeutic option for each affected woman suffering from OC. In recent years, Mexico has made contributions to the PM of OC; however, it still has a long way to go for its full implementation in the country’s health system.

Keywords: Personalized medicine; Ovarian cancer; Targeted therapies; Mexico

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Ovarian cancer (OC) is the eighth leading cause of cancer death among women worldwide and the sixth in Mexico. The incidence of OC increases over the women’s lives and about half of them are 63 years or older [1]. Estimations of incidence, mortality and prevalence for OC can be visualized in Table 1 [2].

Click to view | Table 1. OC in Numbers in Mexico and the World According to Globocan 2018 |

Ovarian carcinomas are a heterogeneous group of neoplasms that are generally classified based on type and degree of differentiation (tumor grade). Early diagnosis is a challenge due to the lack of pathognomonic signs and symptoms for this condition. Most of the time these malignancies are detected after the disease has already spread beyond the pelvis (stage III-IV) with a survival rate or 20% or less [3].

About 85-90% of malignant OC cases correspond to epithelial ovarian carcinomas that can be classified into four different types: serous carcinomas (52%), clear cell carcinoma (6%), mucinous carcinoma (6%) and endometrioid carcinoma (10%) [4].

The standard initial management of epithelial OC consists of surgical staging, operative tumor debulking and administration of chemotherapy. Conventional chemotherapy is a platinum/taxane regime, although, depending on the type of OC and its molecular profile, different types of chemotherapy drugs can be used. Adverse side effects, resistance, and recurrence of the disease after chemotherapy are major reasons to use targeted therapies; personalized medicine (PM) has a higher chance to effectively combat the tumor [5].

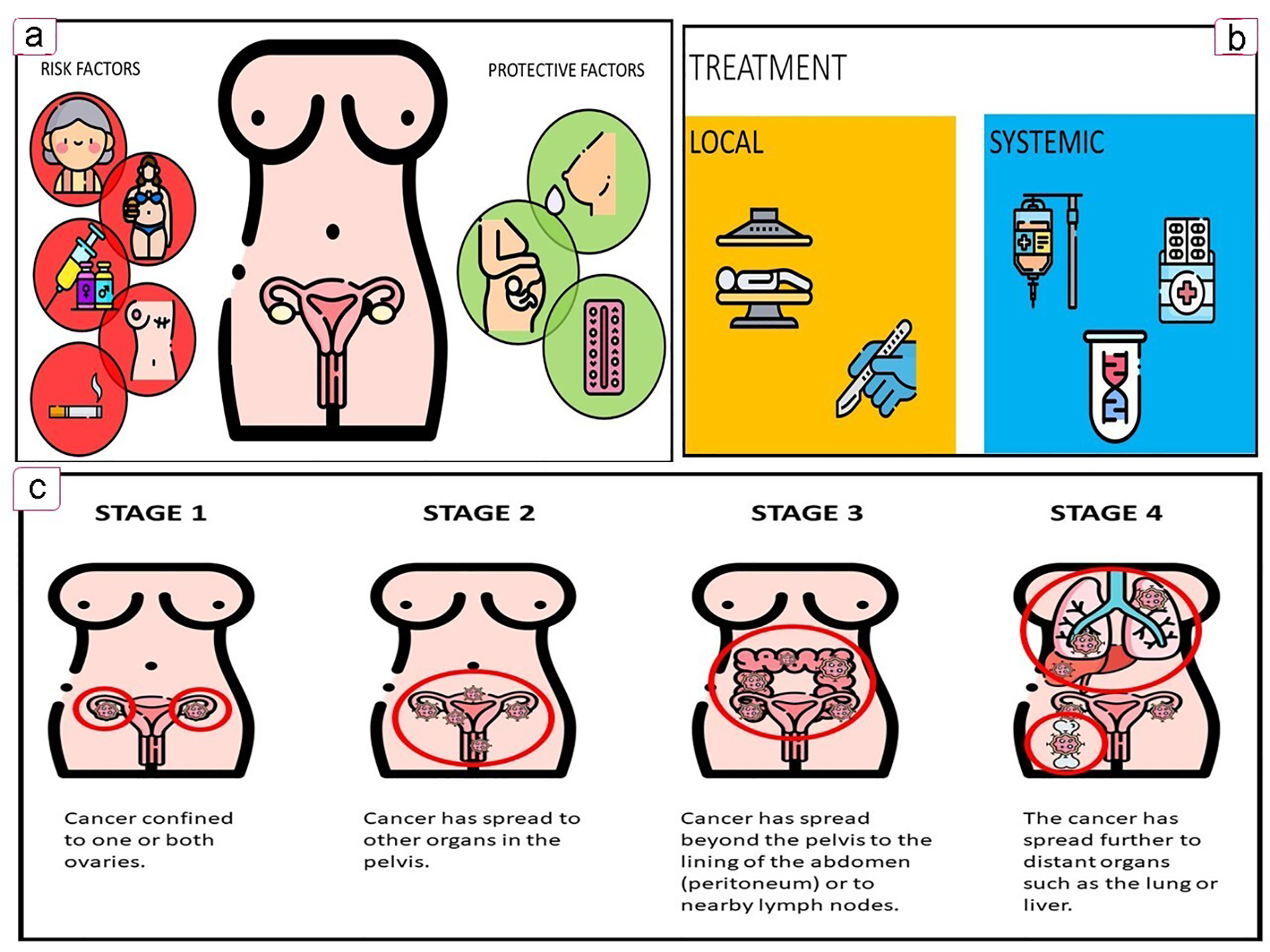

Current clinical and classification therapeutic hallmarks of OC are summarized in Figure 1.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Key features of OC. (a) Associated factors. (b) Treatment options. (c) OC FIGO staging. OC: ovarian cancer. |

| The Role of Genetics in OC | ▴Top |

The comprehensive genomic analyses of tumors using next generation sequencing (NGS) technology by the collaborative network of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) have drawn genetic landscapes and molecular profiles for different types of cancers, with a central goal of identifying new potential therapeutic targets.

In 2011, TCGA deciphered the genome of the OC by analyzing 489 tumoral samples of high-grade serious OC and revealed a particular signature of genes found significantly mutated: TP53 (96%), BRCA1 (9%) and BRCA2 (8%). Other six significantly associated genes were: CSMD3, NF1, CDK12, FAT3, GABRA6 and RB1 [6].

The comprehensive molecular profiling of patient tumors has accelerated the adoption of PM in oncology. When analyzing gene activity patterns, one expression signature of 108 genes was found to be associated with a poor patient survival period. Specific molecular profiles such as particular gene mutations, distinctive transcriptional patterns and altered cellular signaling pathways play a pivotal role in the design of targeted therapies [6].

| PM | ▴Top |

The US National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), an institute from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), defines the PM as an emerging practice of medicine that uses an individual’s genetic profile to guide medical decisions for the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of a disease [7]. PM is also called precision medicine, individualized medicine, stratified medicine, targeted medicine and genomic medicine.

Even before the Human Genome Project was launched (three decades ago), a decade and a half earlier a pioneering genomic sequencing project in which one of the authors participated (HAB-S) explored the potential value of genomic knowledge into clinical diagnostic tests to predict response to treatments utilizing a particular genomic feature. This first translational research in genomics was possibly thanks to the achievement of the world record for sequencing the largest piece of the human genome that corresponds to the growth hormone locus [8]. It consisted in the invention of a polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based predictive test for the response to the treatment with recombinant growth hormone.

In recent years, PM has made considerable progress in the diagnosis and treatment of gynecological cancers. Table 2 [9-26] shows some relevant advances of PM in OC.

Click to view | Table 2. Milestones in PM of OC |

It is well known that genetic background plays an important role in the genesis of OC. The Data Portal of the National Cancer Institute “Genomic Data Commons” harbors a collection of 3,401 characterized cases of OC, of which only 64 (1.8%) correspond to Hispanic or Latino ethnicity [27], which indicates the need for such studies as a prerequisite to bringing the promise of PM to this ethnicity.

PM by allowing to match each patient’s genome with the right treatment (at the right dose) [27], has made a case in breast and ovarian tumors. Women affected by these tumors frequently carry mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. These genes produce tumor suppressor proteins that help repair damaged deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and thus ensure the genetic stability of the cell. But when cancer cells carry mutated versions of these genes, they become more sensitive to anticancer agents that act by damaging DNA, such as cisplatin. In this sense, drugs directed to inhibit the only other DNA repairing mechanism left, the poly (ADP ribose) polymerase (PARP), have been found to arrest the growth of said BRCA-mutated cancer cells [28]. The benefit of BRCA testing is to determine the feasibility to draw upon this approach to effectively combat these cancers. AncestryDNA, Helix and 23andMe are international biotech companies offering BRCA testing, while in Mexico, companies like ours (Vitagenesis) offer BRCA testing as a companion diagnostics. Other predictive molecular testing biomarkers for OC include genes like ATM, BRiP1, CHEK2, PALB2, RAD51C and RAD51D.

| Mexico in the Fight Against OC | ▴Top |

In Mexico, cancer mortality has had a rising trend, and the same applies to OC. A study lead by Gomez-Dantes et al stated that the population growth contributed to a 36% increase in OC deaths between 1990 and 2013 [29].

Since 2016, the Mexican government has provided support for the fight against OC by the promotion of campaigns for its detection alluding to the International OC Day (May 8). Moreover, in 2018, 15 Mexican medical institutions were certified by the Ministry of Health to serve OC patients with full coverage by the Seguro Popular (just recently replaced by the National Institute of Health for Wellness), with at least one of each located in the following Mexican states: Campeche, Chiapas, Chihuahua, Colima, Durango, Estado de Mexico, Guanajuato, Jalisco, Queretaro, San Luis Potosi, Tamaulipas and Yucatan.

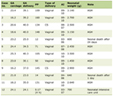

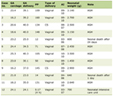

Clinical trials within research institutions are essential in the development of PM. However, currently, there are only four active clinical studies involving Mexican institutions, patients diagnosed with OC and registered in the NIH. Two of them focused on treatment, one more on diagnosis techniques and finally one on the treatment of thrombocytopenia as an adverse effect of chemotherapy. Table 3 [30] enlists the OC clinical studies in which Mexico is participating.

Click to view | Table 3. Current Clinical Studies for OC in Mexico [30] |

| Achievements of the PM in Mexico | ▴Top |

Several milestones have contributed to the emergence of PM in Mexico. After creating the first center in Latin-America dedicated to genomics, the Center for Genomic Biotechnology of the National Polytechnic Institute in 1999, our preceding academic laboratory joined the planning committee that proposed the creation of the National Institute of Genomic Medicine (Instituto Nacional de Medicina Genomica) that was inaugurated in 2004. Its mission calls for contributing to the Mexican health system by developing scientific research leading to the medical application of genomic knowledge through cutting-edge technology in this new scientific discipline.

Later in 2014, the Latin American Association of Personalized Medicine (ALAMP, for its acronym in Spanish) was founded in Mexico City to promote personalized treatments based on the molecular profile.

And more recently, in an effort to promote the development and technological modernization of Mexico, the National Council on Science and Technology (Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnologia, CONACyT) established the National Laboratories that promote PM such as the National Laboratory of Personalized Medicine (LAMPER) and ours National Laboratory for Specialized Research, Development and Innovation Services (LANSEIDI), whose main objectives are to offer: 1) Highly specialized services; 2) High-level training of human resources (masters and doctors in biotechnological innovation, human genetics, and PM); 3) Collaborations with government, industry, academia and society; and 4) State-of-the-art R&D in PM.

Regarding efforts to bring the promise of PM to OC Mexican patients, key milestones are: 1) The description of the first Mexican founder BRCA1 mutation, ex9-12del, germline deletion of exons 9-12 [31]; 2) The formulation of an anti-angiopoietin therapy with trebananib for recurrent OC [32]; 3) The detection of BRCAs mutations in 28% (26/92) of a cohort of OC cases in 2015 [22]; 4) The development of a simple and low-cost screening method for the Mexican founder mutation (BRCA1 ex9-12del) based on quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) [33]; 5) The role of microRNAs in its angiogenesis [34]; 6) The characterization of let-7d-3p in the apoptosis and sensitization to chemotherapy in OC cells [35]; 7) The identification of the proteomic profile of ascites in epithelial OC [36]; 8) The identification of 76 polymorphic variants in northeast Mexican patients with sporadic OC (50 of those variants were not previously reported) [26]; 8) The discovery of molecular components involved in OC pathogenesis, such as the hypoxia-regulated miRNAs (HypoxamiRs) Profiling Identify, that identified the miR-765 as a regulator of the early stages of tumor vasculogenesis [37] to mention one.

| Challenges of the PM in Mexico | ▴Top |

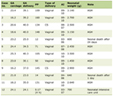

Table 4 describes the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved drugs for the treatment of OC, highlighting the current three approved anti-PARP therapies: Olaparib (Lynparza), Rucaparib (Rubraca) and Niraparib (Zejula) [38]. So far, only Olaparib has been introduced to our country.

Click to view | Table 4. FDA-Approved Drugs for the Treatment of OC [38] |

The conventional treatments are usually tested on broad populations and are prescribed based on statistical averages. Sometimes this works effectively in some patients but not for some others due to the differences at the genome level. Recently, it has been growing the development of advancements of these differences thanks to the omics technologies (genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics and metabolomics). Those advances have shown a wide variability of cancer molecular profiles, including the OC. In addition to the correct choice of treatment according to the molecular profile of cancer, it is mandatory to take into account pharmacoeconomic considerations in order to cope with such expensive treatments and diagnostic techniques in health systems [39].

Mexican patients affected by OC can profit from PM by gaining access to individualized diagnosis to stratify them according to treatment options, while care providers will be able to better predict effective treatment for their diseases, leading to optimization of time, costs, safety and efficacy of health care. For all those reasons, it is a priority for our National Health System to increase genetic assessment in the near future.

| Genetic Counseling: The Big Next Step for a PM in Mexico | ▴Top |

The US National Society of Genetic Counselors defines genetic counselors as professionals who have specialized education in genetics and counseling to provide personalized guidance to patients for making decisions about their genetic condition. Their role is to analyze personal and family medical records, execute a risk assessment, advice about the advantages and limitations of genetic testing, help in decision making and support psychosocially these patients [40].

Genetic counseling is a well-known medical specialty in first-world countries, such as Canada, the USA and the European Union. However, Mexico has not adopted genetic counseling as a separate profession, and across 32 Mexican states, only Mexico City has at least one medical geneticist per 100,000 inhabitants [41]. Mexico has not yet adopted genetic counselor as a separate profession, with the medical geneticists providing these services [41]. Although there have been advances in recognizing the importance of genetic counseling in Mexico, the country is lacking infrastructure for genetic services. The lack of genetic services and the deficient knowledge about the field is a public health concern related to geographic diversity and the high concentration of geneticists and infrastructure in only the capital of the country. The correct use of counseling has the power to help address the issues related to the limited access of genetic services in the country providing an additional type of healthcare; in this way, genetic counselors could be able to prevent cancer deaths that occur due to some types of cancers with a major hereditable risk (estimated in about 14%) [42].

Mexico has the potential to access genetic counseling services such as other countries with similar income; for example, in other upper-middle-income countries (Malaysia, Cuba and South Africa) and even in low-income countries (India and Indonesia), genetic counselors play an important role, either independently or alongside physicians, as part of a multidisciplinary team [41].

| Conclusions | ▴Top |

Nowadays, cutting-edge molecular tools are part of routine health care and the forthcoming of cancer diagnostic by providing insights towards personalized therapy.

Gynecological cancers can also benefit from these insights, especially OC, which represents a serious worldwide health problem in women because of its heterogeneous molecular composition and unavailable effective diagnosis. PM can improve diagnosis, prognosis and prediction in OC by stratifying patients according to their molecular profile. Recently, Mexico has made progress towards the implementation of PM in its health system. However, it still has a long way to go.

Acknowledgments

LEFG thanks CONACyT for his assistantship as an assistant to Level 3 National Research.

Financial Disclosure

No financial support was taken for this research.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest in carrying out this research.

Author Contributions

LEFG: conceptualization, writing, review, editing and design of figures and tables; IGDV: conceptualization, writing, review, editing and design of tables; JGM: writing, editing and design of tables; EAVA: writing, editing and design of tables; SABB: review, editing and design of figures; HABS: conceptualization, writing, review, editing, funding and responsible for the overall content.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Abbreviations

OC: ovarian cancer; PM: personalized medicine; NGS: Next Generation Sequencing; TCGA: The Cancer Genome Atlas; NHGRI: National Human Genome Research Institute; NIH: National Institutes of Health; DNA: deoxyribonucleic acid; PARP: poly (ADP ribose) polymerase; LAMP: Latin American Association of Personalized Medicine; CONACyT: National Council on Science and Technology; LAMPER: National Laboratory of Personalized Medicine; LANSEIDI: National Laboratory for Specialized Research, Development and Innovation Services; qPCR: quantitative polymerase chain reaction; HypoxamiRs: hypoxia-regulated miRNAs; FDA: Food and Drug Administration

| References | ▴Top |

- America Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Ovarian Cancer [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Dec 15]. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/ovarian-cancer/about/key-statistics.html.

- Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, Colombet M, Mery L, Pineros M, et al. Global cancer observatory: cancer today. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2018.

- Elias KM, Guo J, Bast RC, Jr. Early detection of ovarian cancer. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2018;32(6):903-914.

doi pubmed - American Cancer Society. What is Ovarian Cancer? [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Nov 19]. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancer-basics/what-is-cancer.html.

- Cortez AJ, Tudrej P, Kujawa KA, Lisowska KM. Advances in ovarian cancer therapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2018;81(1):17-38.

doi pubmed - The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011;474(7353):609-615.

doi pubmed - NHGRI. Personalized Medicine | Talking Glossary of Genetic Terms | NHGRI.

- Barrera-Saldana HA. Origin of personalized medicine in pioneering, passionate, genomic research. Genomics. 2020;112(1):721-728.

doi pubmed - Micha JP, Goldstein BH, Rettenmaier MA, Genesen M, Graham C, Bader K, Lopez KL, et al. A phase II study of outpatient first-line paclitaxel, carboplatin, and bevacizumab for advanced-stage epithelial ovarian, peritoneal, and fallopian tube cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007;17(4):771-776.

doi pubmed - Skates SJ, Drescher CW, Isaacs C, Schildkraut JM, Armstrong DK, Buys SS, et al. A prospective multi-center ovarian cancer screening study in women at increased risk. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25(18S):5510.

doi - Goff BA, Mandel LS, Drescher CW, Urban N, Gough S, Schurman KM, Patras J, et al. Development of an ovarian cancer symptom index: possibilities for earlier detection. Cancer. 2007;109(2):221-227.

doi pubmed - Moore RG, Brown AK, Miller MC, Skates S, Allard WJ, Verch T, Steinhoff M, et al. The use of multiple novel tumor biomarkers for the detection of ovarian carcinoma in patients with a pelvic mass. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;108(2):402-408.

doi pubmed - Fong PC, Boss DS, Carden CP, Roelvink M, De Greve J, Gourley CM, et al. AZD2281 (KU-0059436), a PARP (poly ADP-ribose polymerase) inhibitor with single agent anticancer activity in patients with BRCA deficient ovarian cancer: Results from a phase 1 study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15S):Abstract 5510.

doi - Burger RA, Brady MF, Bookman MA, Walker JL, Homesley HD, Fowler J, et al. Phase III trial of bevacizumab (BEV) in the primary treatment of advanced epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC), primary peritoneal cancer (PPC), or fallopian tube cancer (FTC): A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(18S):LBA1.

doi - Bahubeshi A, Tischkowitz M, Foulkes WD. miRNA processing and human cancer: DICER1 cuts the mustard. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(111):111ps146.

doi pubmed - Di Nicolantonio F, Arena S, Tabernero J, Grosso S, Molinari F, Macarulla T, Russo M, et al. Deregulation of the PI3K and KRAS signaling pathways in human cancer cells determines their response to everolimus. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(8):2858-2866.

doi pubmed - Vergote I, Trope CG, Amant F, Kristensen GB, Ehlen T, Johnson N, Verheijen RH, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy or primary surgery in stage IIIC or IV ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(10):943-953.

doi pubmed - Patch AM, Christie EL, Etemadmoghadam D, Garsed DW, George J, Fereday S, Nones K, et al. Whole-genome characterization of chemoresistant ovarian cancer. Nature. 2015;521(7553):489-494.

doi pubmed - Liu Y, Yasukawa M, Chen K, Hu L, Broaddus RR, Ding L, Mardis ER, et al. Association of somatic mutations of ADAMTS genes with chemotherapy sensitivity and survival in high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(4):486-494.

doi pubmed - Disis ML, Patel MR, Pant S, Infante JR, Lockhart AC, Kelly K, et al. Avelumab (MSB0010718C), an anti-PD-L1 antibody, in patients with previously treated, recurrent or refractory ovarian cancer: A phase Ib, open-label expansion trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;(15S):Abstract 5509.

doi - Bitler BG, Aird KM, Garipov A, Li H, Amatangelo M, Kossenkov AV, Schultz DC, et al. Synthetic lethality by targeting EZH2 methyltransferase activity in ARID1A-mutated cancers. Nat Med. 2015;21(3):231-238.

doi pubmed - Villarreal-Garza C, Alvarez-Gomez RM, Perez-Plasencia C, Herrera LA, Herzog J, Castillo D, Mohar A, et al. Significant clinical impact of recurrent BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Mexico. Cancer. 2015;121(3):372-378.

doi pubmed - Eeles RA, Morden JP, Gore M, Mansi J, Glees J, Wenczl M, et al. Adjuvant hormone therapy may improve survival in epithelial ovarian cancer: results of the AHT randomized trial. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey. 2016;71(4):223-224.

doi - Uzilov AV, Ding W, Fink MY, Antipin Y, Brohl AS, Davis C, Lau CY, et al. Development and clinical application of an integrative genomic approach to personalized cancer therapy. Genome Med. 2016;8(1):62.

doi pubmed - Patel JM, Knopf J, Reiner E, Bossuyt V, Epstein L, DiGiovanna M, Chung G, et al. Mutation based treatment recommendations from next generation sequencing data: a comparison of web tools. Oncotarget. 2016;7(16):22064-22076.

doi pubmed - Delgado-Balderas JR, Garza-Rodriguez ML, Gomez-Macias GS, Barboza-Quintana A, Barboza-Quintana O, Cerda-Flores RM, Miranda-Maldonado I, et al. Description of genetic variants in BRCA genes in mexican patients with ovarian cancer: a first step towards implementing personalized medicine. Genes (Basel). 2018;9(7).

doi pubmed - Grossman RL, Heath AP, Ferretti V, Varmus HE, Lowy DR, Kibbe WA, Staudt LM. Toward a Shared Vision for Cancer Genomic Data. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(12):1109-1112.

doi pubmed - Jain KK. Textbook of Personalized Medicine. 2nd ed. Humana Press; 2015.

doi - Gomez-Dantes H, Lamadrid-Figueroa H, Cahuana-Hurtado L, Silverman-Retana O, Montero P, Gonzalez-Robledo MC, Fitzmaurice C, et al. The burden of cancer in Mexico, 1990-2013. Salud Publica Mex. 2016;58(2):118-131.

doi pubmed - Clinical trials - Search for Ovarian Cancer and Mexico. [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Oct 22]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=ovarian+cancer+&term=&cntry=MX&state=&city=&dist=.

- Weitzel JN, Lagos VI, Herzog JS, Judkins T, Hendrickson B, Ho JS, Ricker CN, et al. Evidence for common ancestral origin of a recurring BRCA1 genomic rearrangement identified in high-risk Hispanic families. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(8):1615-1620.

doi pubmed - Monk BJ, Poveda A, Vergote I, Raspagliesi F, Fujiwara K, Bae DS, Oaknin A, et al. Anti-angiopoietin therapy with trebananib for recurrent ovarian cancer (TRINOVA-1): a randomised, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(8):799-808.

doi - Martinez-Trevino DA, Leon-Cachon RBR, Villarreal-Garza C, Aguilar YMD, Aguilar-Martinez E, Barrera-Saldana HA. A novel method to detect the Mexican founder mutation BRCA1 ex912del associated with breast and ovarian cancer using quantitative polymerase chain reaction and TaqMan(R) probes. Mol Med Rep. 2018;18(2):1531-1537.

doi pubmed - Flores-Perez A, Rincon DG, Ruiz-Garcia E, Echavarria R, Marchat LA, Alvarez-Sanchez E, Lopez-Camarillo C. Angiogenesis analysis by in vitro coculture assays in transwell chambers in ovarian cancer. Methods Mol Biol. 2018;1699:179-186.

doi pubmed - Garcia-Vazquez R, Gallardo Rincon D, Ruiz-Garcia E, Meneses Garcia A, Hernandez De La Cruz ON, Astudillo-De La Vega H, Isla-Ortiz D, et al. let-7d-3p is associated with apoptosis and response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in ovarian cancer. Oncol Rep. 2018;39(6):3086-3094.

- Toledo-Leyva A, Villegas-Pineda JC, Encarnacion-Guevara S, Gallardo-Rincon D, Talamas-Rohana P. Effect of ovarian cancer ascites on SKOV-3 cells proteome: new proteins associated with aggressive phenotype in epithelial ovarian cancer. Proteome Sci. 2018;16:3.

doi pubmed - Salinas-Vera YM, Gallardo-Rincon D, Garcia-Vazquez R, Hernandez-de la Cruz ON, Marchat LA, Gonzalez-Barrios JA, Ruiz-Garcia E, et al. HypoxamiRs Profiling Identify miR-765 as a Regulator of the Early Stages of Vasculogenic Mimicry in SKOV3 Ovarian Cancer Cells. Front Oncol. 2019;9:381.

doi pubmed - FDA. FDA Approved Drug Products: Database. 2017.

- Barrera-Saldana H, Sanchez-Ibarra H, Trevino-Saenz D, Fernandez-Garza LE. Pharmacoeconomics of metastatic colorectal cancer treatment with targeted therapies guided by companion molecular diagnostics. Journal of Pharmaceutical Research and Therapeutics. 2020;1(3):124-129.

- Jamal L, Schupmann W, Berkman BE. An ethical framework for genetic counseling in the genomic era. J Genet Couns. 2020;29(5):718-727.

doi pubmed - Bucio D, Ormond KE, Hernandez D, Bustamante CD, Lopez Pineda A. A genetic counseling needs assessment of Mexico. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2019;7(5):e668.

doi pubmed - Practice-based competencies for genetic counselors. Accreditation Council for Genetic Counseling. 2015:1-9.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

World Journal of Oncology is published by Elmer Press Inc.